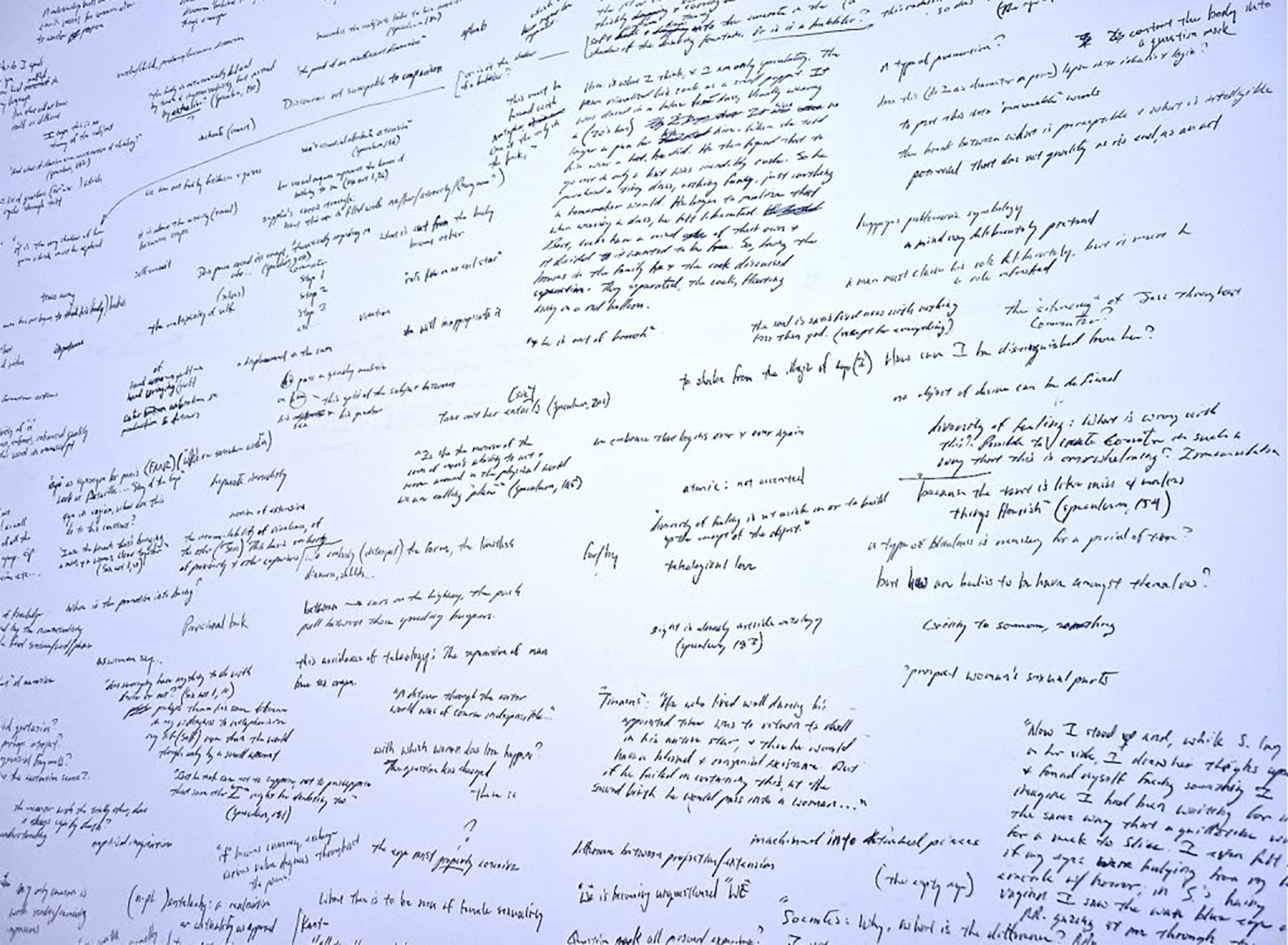

Hand-written manuscript of Commuter

James Belflower is the author of Commuter (Instance Press) and And Also a Fountain, (NeOpepper Press) a collaborative echap with Anne Heide and J. Michael Martinez. Commuter was recently voted 2009’s “Best Book Length Long Poem/Sequence” by ColdFront magazine. His work appears, or is forthcoming in: EOAGH, Denver Quarterly, Apostrophe Cast & Greatcoat among others. He curates PotLatchpoetry.org, a website dedicated to the gifting & exchange of poetry resources.

Interview by Rachel Cole Dalamangas

Your collection, Commuter is a poetry of urban disaster, or more specifically, the detonation of a terrorist bomb—essentially, the poetry of an event. What do you think is the influence of 9/11 and the “War on Terrorism” and methods of contemporary warfare on language? On art’s concerns with consciousness? Do you think violence changes how we shape our questions about beauty?

I like your description of Commuter as “a poetry of an event.” I wonder if it might be even more accurate to describe it as a poetry of event. In this case, the event is the dissolution, dislocation and withdrawal—coexistent with the rethinking, rewriting and (re)witnessing of a rapidly changing sense of what constitutes relation and to a broader extent, community. Commuter attempts to (as you suggest below in some cases “aggressively”), enact an event of discourse and relation in this intersection. A discourse that resists the logic that results in the community of death created by and around suicide bombing.

I think this logic is very common though, and in many instances a symptom of the practice of poetry of witness (and arguably of poetry in general). So, the other primary concern was refusing this thinking. In many cases poetry of witness, and especially poetry of secondary witness, presumes to be a vehicle for the unspeakable, the testimony of those who are silenced. Yet, this logic is a means to an end, almost always that end is the “project,” the communion with another, the making meaning out of what I believe is ultimately utterly meaningless: death. In instrumentalizing another’s death, a text entertains a conception of community similar to that of suicide bombing, both constituted on the value of another’s death: the justification, defense, and potential of death. In one case metaphoric, in another martyrdom.

These logic systems center an understanding of communal structures in an originary essentialist past that only needs to be reconstituted through fusion with another for success. They suggest community as a product. As such, these systems no longer contain the possibility for the “eventness” necessitated by the limit(s) that a community is. Expanding on Maurice Blanchot, Jean Luc-Nancy calls it an “unworking” of community. I’ll quote him so I don’t botch it too badly, “that community, in its infinite resistance to everything that would bring it to completion signifies an irrepressible political exigency, and that this exigency in its turn demands something of ‘literature,’ the inscription of our infinite resistance.”

To make a long answer longer, but hopefully to answer your question, this exigency and “infinite resistance” must reshape our questions about beauty. In the pressurized space of a tradition that attempts to situate the beautiful (especially in poetry of witness) on an “authentic” subjectivity, the space for a rearticulation of beauty, much less of trauma is very limited. I personally have a very fraught relationship to beauty, in many cases finding it to be a default aesthetic mode for much poetic witness: when the trauma gets tough, the trauma turns beautiful. It seems that poetry of witness generally doesn’t interrogate the implications of beautifying atrocity very often, usually relying instead on an empathetic response that has strong affinities with the sentimental tradition. This understanding of beauty is unable to account for the unnerving experience of such works as Charles Reznikoff’s Holocaust, Charlotte Delbo’s trilogy Auschwitz and After, M. NourbeSe Philip’s Zong!, Rachel Zolf’s The Neighbour Procedure or Vanessa Place’s, The Guilt Project, much less the events that these texts strive to express.

So a main question for me became, how to think/write with the full awareness of my own complicity in all of these issues, what Nancy calls a “literary communism.” I like the emphasis he places on the idea of offering texts to communication, a certain manner of sharing that the text enters. What is important to this idea is abandonment. In offering something, you abandon it at the same time. Commuter seeks to populate this limit. In some sense this extends to a certain description of thinking as care for another: the offering/abandonment of a text in/as an uncrossable threshold, where the text becomes, not exactly a common ground, but a meeting place nonetheless. And the process of the work changes then, it commutes, (especially in the sense of a traveler, and the alteration of a period of imprisonment) a discourse as part of a communal formation: it is preoccupied with the unending travel(er) of/on communication.

The Prologue locates us in the chaos, panic and fragmentation of a destroyed urban space. There are people “combing hospitals,” architecture goes rickety, time is being counted and noted—these elements of a walk through the city, architecture, and time are all hallmarks of surrealism and the New York schools of poetry. How influenced are you by surrealist poets and/or NY school poets?

Well, you caught me; I do absolutely love Frank O’Hara. That being said, my concern about reading the book as surrealist would be surrealism’s emphasis on irrationality, or nonrationality that seem like a less than rigorous response to the horrors that took place in reality, and their eventness in Commuter. As I mentioned above, emulating purely rational thinking also doesn’t seem to be the answer. Perhaps there are alternatives?

As I think your question indicates, surrealist logic on one level could account for Commuter in some ways, and they both use similar techniques. It is, in a certain sense about someone shooting a revolver into a crowd. However, in response to the seeming irrationality, or dream like quality of the events there is a care for the reader and victim, an attempt to come alongside, to meet him or her in the event(s) of witnessing writing/trauma that is ongoing.

This question comes to a head in the work on page 73 where I insist that these events were not hallucinations and ask the reader to write paragraphs containing certain words having to do with dream narrative and such.

My other concern was a refusal of the solipsistic and ironic positions that preoccupy much of the pseudo-surrealist poetry that has been very popular for awhile now.

It may be a more helpful framework to consider these themes through the context of the Situationist International, specifically their ideas of psychogeography and the dérive. Debord’s description of the dérive is a very accurate description of Commuter: “a technique of rapid passages through varied ambiences.”

The work slips between what sounds like journalistic reporting and broken, breathy poetry. What is the relationship between poetry and “reporting” on the world?

“Breathy,” hmm… I can see where you could say that. I was thinking more of an out-of-breathness, rather than breathy poetry, since you mention its brokenness also. I was reading Kenneth Patchen’s Panels for the Walls of Heaven recently and was struck by his long, long, extended and barreling lines that forced the reader to alter his/her breathing. It was as if Patchen’s thought accumulated at a different speed than the readers breathing rhythm. As a result, I could no longer breath where I wanted to. This became integral to the project because, for me, the extension, or overextension of the breath mimicked the incommunicability of many of the traumatic events in the work. Altering your breathing pattern causes you to become immediately conscious of it. As awareness of breathing enters thought, it becomes irregular: how many times have you tripped over your breathing the moment you thought about it? In some sense, this is comparable to the way that you become conscious of another person. There is a sensing of patterns, which at the same time, disrupts those patterns. He/she has been there all the time but an alteration on your part causes you to listen differently. I think the differences you’ve pointed to speak to this very well. It is about the passage between very different conversations, in this case poetry and reporting, that (like the breath) only interrupt our awareness when they are disrupted. Considering their proximity on the page, it becomes necessary to continue that interruption/passage, rather than end its relationship.

- NourbeSe Philip’s Zong! is an amazing example of this (dis)embodiment, showing the limits of the breath. She splits words across the page, but maintains a narrative, so that as you’re reading, your sense-making is completely at odds with your breathing and is spaced very differently than you’re accustomed to. It’s a wonderful technique and complicates a simplistic embodiment of the work.

Given that this work places a heavy emphasis on the materiality of the page as well as how the work is performed/experienced, where/when do you locate the event of poetry itself?

Primarily in interruption and failure. I think poetry has the capacity to interrupt first its own mythologies/ideologies and to a broader extent, the mythologies/ideologies that govern much language usage and thinking today.

I view Commuter first and foremost as a process, but this process is one of perpetual interruption: of itself, of events, of thought process, of reader expectation and writing. In this case, it is an interruption of a signifying practice that locates the possibility of the representation of trauma through language, especially one based on an “empathetic” stance that attempts to understand the other through a recognition of similar experience: you’re human, I’m human, therefore I understand what you’re going through.

However, something I consistently grapple with is how to relate motile process to what seems to be the utter stasis of death. Is there relation of a different sort here, and if so, how can one write this relation? In some sense, it returns to the question of community. If our access to the other is through death, then what manner of access is this?

As far as failure is concerned the book purposely foregrounds its failure to “represent” trauma and all its effects through language. However, it is this failure, or the continuous contention with this failure, that generates and supports the community I’m suggesting and places a large responsibility on the reader as a member of this community. To be more specific, the book’s response to atrocity is to precisely fail to reconcile it metaphorically or otherwise, (and therefore reduce) a certain usage of trauma by language: a (re)production of trauma through a certain logic of expression. I’m always hesitant to suggest that trauma can be cast into (a) language, or should be for that matter, but that doesn’t mean it shouldn’t be written.

The book practices a thinking that envisions witnessing as an awareness of singular events in contact, not in communion: whether these events are love, atrocity or anything in between. In some sense a thinking in contradictions, rather than through them. I don’t mean to suggest that relation isn’t happening but it is a relation supported only by this incessant “communication.” And this communication is in the form of an interruption of the assumption that we are fully sharing, to the point of knowing, another’s experience. In some sense it is a contact with the limit that is/is not another’s singularity. This is why I keep insisting on the importance of the reader to Commuter. He/she is vital to the social process that is the work. The reader is the 3rd “witness.” In that sense, if a reader is contacted, perhaps the work fails very differently!

After the Prologue—which sounds more journalistic than poetic—Commuter opens with a poem that is essentially instructions for constructing a bomb, and thus the poem becomes not the event but the ignition of an event. There are many things I could say about the idea of a poem-as-detonator but I’d like to start with a metaphysical question about the relationship between events and language: to your mind, does language call events and organized chaos into being or into our awareness of being? Or is language simply a naming system to describe what already is? Is this tension a major concern of your poetry?

I love your distinction between the poem as event and the poem as ignition of an event. I think that this difference is very important for Commuter.

The short answer is yes; this tension is a major concern. I would have to say that I think language names, or more precisely delimits—the unnamable, or for language in general the first order, or to use a risky word, the unconscious. For me, language exposes a threshold. It (de)limits, or chalks communication. In Commuter the relational abundance of “it” speaks to your question. As I’m sure you noticed “it” refers to and can be substituted for any number of referents, signs/signifiers. “It” is a person, a helicopter, a currency etc. So this “name” at once, “calls” events into occurrence and at the same time serves as a threshold, or chalk line, albeit a loose (and in this case jarred loose) one, for event(s). These aren’t necessarily traumatic events but trauma usually communicates these limits more clearly than other discourses. But here is the challenge: part of the project was to activate, or as you put it, ignite this abundance, to write in a way that precisely emphasized the potential of the word, prior to its manifestation as a threshold. What I was in part, trying to touch upon was what Deleuze calls “order-words.” Words that relate to and ignite implicit presuppositions in the reader. In some sense, this confronted the impossibility of communicating my own, and another’s mortality through this precise failure to situate, or name, in the sense of commune with, understand, or essentialize identities within the poem. The radically provisional quality of these order words, whether they are more associated with discourses of trauma, another person, a lover, or quotidian life, also abundantly “name” various other events for the author, victim and reader. This abundance necessitates similar event of the crises of naming on the part of the reader.

MacLow’s idea of “controlled hysteria” is important here also. He mentions the features of this hysteria as barely controlled emotional outbursts, sometimes appearing aggressive or angry. What is most important to Commuter though is his last feature, suspense. In an analogy to the order word, the reader senses that this outburst is almost uncontrollable, it appears at its limit of containment, it’s suspended, or as we said above, it delimits the event. Interestingly enough he calls it a very “theatrical” experience.

The language of Commuter is both expressive of empathy for those who are victims of terrorism and is highly descriptive of violence—balancing both extremes while managing to produce quite beautiful phrasing. When writing Commuter, did you have ethical concerns about working the event of trauma into the texture of poetic beauty?

I’m hoping that this question is in part answered by your question about rethinking beauty. But to expand on it more, yes, absolutely I have ethical concerns. One of the biggest challenges for me is the risk and implications involved in secondary witnessing. Although I’m as unsure as I am convinced that it is necessary, it is an incredibly provisional practice. One idea that bothered me was that in the context of witnessing, received semiotic use becomes especially problematic in the representation of another. That is the reason for many of the crossed out words, which also equate this problematic mythology/ideology of beauty with the equally problematic mythology/ideology associated with the romanticization of the femme fatale.

I’ll return to this idea of infinite resistance also. As far as an ethics of this text is concerned, I would argue that this resistance translates to the reader through the author. First in the reader’s experience of the author’s fragmentary responses, and secondly in his initial inclination (and the author’s) to combine or fuse these events. Both of these events are results of a reader’s reading habits, especially combined with the expectations of poetry that deals with atrocity. So this infinite resistance begins in the text and continues into the reader, who as a 3rd party, is asked to participate in the writing of the text itself. Though the reader’s relationship to the text changes, the suspension of his/her ability to connect or link events in the text becomes the primary mode of relation within the text. Sometimes forcefully, the reader is asked to share, to communicate (in) this suspension, to both found and be complicit in this “community.” He or she is asked to be unsuitable to “witness” the author’s inability to witness/commune with these events, to come alongside him and to distribute these events in an unsuitable semantic system.

In addition to gaps in the page, gaps between words, partially erased words, lines stricken-through, there is a brokenness or disjoint or strangeness between how subjects and objects relate in the post-bomb language of Commuter. For example, on page 60 are the lines, “clearer to / frame you / behind the reason / I fisted a door?” I’m not sure whether “fisted a door” is just an odd , condensed way to say something synonymous along the lines of, “I put my fist through a door,” as an expression of violence or anger, or whether it’s intended to reference the extreme sexual practice of “fisting” (which would be surrealist—essentially, sadomasochistic sex with architecture—which is sort of incredible as imagery of terrorism). I interpret that it is the double-entendre that is important here as shards of phrasing and syntax reform to make a new, odd, off-ish sense of each other. Why does the fragmentary, disoriented (but still precise) language of trauma belong in the realm of poetry for you?

I think it’s Kristeva who says it and her description applies very well here. She says that process as practice is always an extreme moment. Language is/as a form of violence . . . Blanchot even suggests that it is a form of terrorism. I’m not sure these are answers to your questions but I think they provide a framework for the phrase you excerpted. I’ll also have to refer to the interruption, or disruption we talked about earlier.

I like your reading of this very much and yes, as a short answer it is about that odd-offish sense. Part of the strangeness of this figuration comes from thinking of the practice of poetry of witness as a masochistic act, understood as very different from a sadomasochistic one. I’m working on a paper now that analogizes the process of poetry of witness with a masochistic relationship: it relies on a certain power dynamic between pain and/or trauma to the author: specifically on the generally expunged element of desire combined with the illusion of the (author’s) powerlessness, in the aesthetization of traumatic events. But this recognition of the power structures in a masochistic relation also provides great potential for rethinking identity formation, community and sexual politics.

The work is aggressive, most obviously in the directions to the performer that are scattered through the pages. I admit I felt even a bit uncomfortable when I encountered the list of immediate family and close friends on page 40 with the footnote instructing the reader to cross-out those names and replace with others. How much is this about subjecting the reader to a kind of objectification or about making the reader complicit in the activity of the poetry?

I’m so excited you felt uncomfortable! What a huge compliment! I also hoping that you felt invited, to be a part of the text, to perform it. I would say it is both of these things: complicity, which we discussed beforehand, extends to the author as well as the performer. I’ve called them the reader in this interview but you bring up the very important distinction Commuter makes: that of the “performer” as reader. At a very basic level I think this contributes to both the feelings of aggressivity and complicity you noticed, since a reader is not usually accustomed to thinking of the public connotations of him/herself performing a text, in both public and private.

I think to a degree a feeling of objectification is a helpful response to the piece and may indicate the tension within an artwork that Adorno speaks to. However, though objectification may initially be a part of it, I would hope that the extensive questions and invitations to perform, both sustain and recombinate this feeling of objectification with others. Part of that feeling as you said earlier, is that subject/object distinctions seemed to be rather difficult to pinpoint. Agamben in Remnants of Auschwitz discusses the etymology of the word witness and describes one definition as a figure in the position of a 3rd party, someone who for other reasons than trauma, also cannot bear witness. This is where the possibility of secondary or proxy witness appears although it is a highly unstable position.

The juxtapositional quality of the text places the reader in this third position. So, in effect, the reader “witnesses” or dérives the process of both secondary and firsthand witnessing. So to feel uncomfortable here, I think, is a very warranted initial response. Hopefully, as the book encourages relation (as you’ve pointed to), it also initiates other involvement on the part of the reader, namely the ethical tension that their rotating position of witness, secondary witness and objectified other, elicits. Since these positions do not tend toward reconciliation within or outside of the work the reader must persistently contend with them all.

Blazer’s comment about making the poem into “a necessary function of the real, not something added to it” is very important for this involvement.

When I saw you read at the Dikeou Collection a couple summers ago, you used a white noise machine in the background of your reading. Does poetic language ride the white noise? Or rise out of the white noise? Or, as a poet, do you listen into the white noise?

I love drone/noise music, Spaceman 3, Noveller, Skullflower, E.A.R., Kites, Steve Roach, William Basinski, etc. For that project, tentatively titled The Poster of Contour, or 0, (Zero comma) I am experimenting with noise, or more specifically drone, as a platform for the performance of the piece. The work takes vacuums/vacuuming/vacuity and fluid dynamics as primary themes and so the idea of a droned tone as a vacuum, or fluidity allows for a certain affirmative quality to the historically abhorred natural “vacuum.” The idea in part stems from Berio’s Oboe Sequenza. What amazed me about the piece was the droned B that, as the piece progressed, and the oboe counterpointed against the drone, it began to both collapse the piece into an imaginary horizontal line that extended out from its source, and yet at the same time, it filled the room to the point of almost a visual throbbing. It seemed that a vacuum of sorts was created, but one that was fully empty. The oboe counterpoint became a sort of supplement, to this absence, like the language of the poem around a certain immaterial space. Many of Varese’s pieces have a similar visual/auditory effect on me. I guess it is similar to Scriabin’s synesthesia. Is there a specific name for that? The sequenza is fantastic, especially performed live.

In answer to your question, I think it’s both; language both rides and rises out of noise. It’s information theory at it’s most basic, noise coexists with language, music etc. For that performance, I also “listened into” the noise: the tone that droned through the piece was my normal speaking voice, which happens to be approximately an F#. I tried to keep that pitch for many of the sections dealing with vacuums.

What forthcoming projects do we have to look forward to?

At this point, I have two main projects I’m working on, besides my dissertation. One, Friend of Mies Van der Rohe rethinks Heidegger’s concept of dwelling through Philip Johnson’s Glass House. The other, tentatively titled The Posture of Contour, or 0, (Zero Comma) explores those strange registers between the performance qualities of a lecture, a poem and conversation in a David Antin style. There are some wonderful expectations to be disrupted in the contrasts of these genres.